The government’s failure to comply with the coca crops substitution program in Colombia has left the future of almost 100,000 families in limbo and sets up a major setback in the country’s drug policies.

The latest report on the monitoring and verification of the illicit crops substitution commitment issued by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) showcases breaches by the Colombian government within the National Comprehensive Program for the Substitution of Illicit Crops (Programa Nacional Integral de Sustitución de Cultivos Ilícitos – PNIS). This program was a crucial part of the peace agreement reached between the government of former president Juan Manuel Santos’ and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – FARC) in late 2016.

SEE ALSO: Coverage of FARC Peace Process

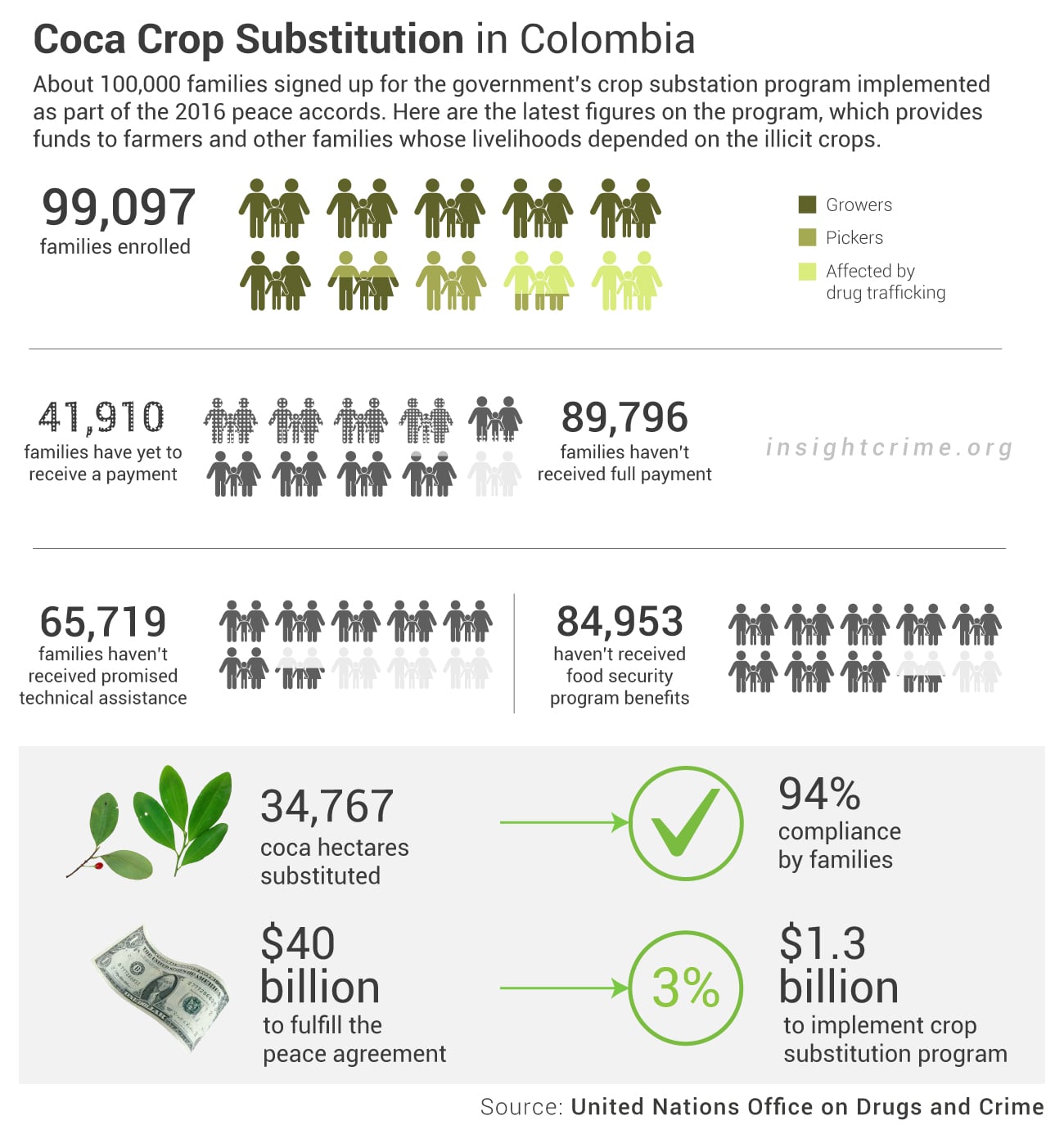

According to the report, few of the 99,097 families enrolled in the program have received the full payments due them and at least 40,000 have not received any payments.

In contrast, 94 percent of the families enrolled in the PNIS have complied with their part of the agreement, which has resulted in the voluntary eradication of almost 35,000 coca hectares, from around 200,000 calculated to exist in the country.

Furthermore, the UNODC also highlights that voluntary substitution has led to a low 0.6 percent replanting rate as opposed to 35 percent in areas where forced eradication programs have taken place.

Yet Duque’s government is broadening the eradication strategy. On this year’s National Development Plan, the coca crops eradication plan was planned for 280,000 hectares, almost 80,000 more than the UNODC estimate.

When questioned about the discrepancy, several officials explained it was due to the soaring replanting rate of forced eradication. In other words, the government is planning to eradicate coca that has not even been planted yet.

Duque has been encouraged by the US government, where President Donald Trump recently stated he would double the budget for the fight against drugs in Colombia if it goes back to the use of glyphosate, suspended since 2015. The Colombian government recently presented a political and media strategy to return to the use of the controversial chemical.

This is despite mounting evidence that the aerial spraying strategy, and forced eradication in general, has been proven ineffective (it is estimated that 30 hectares must be sprayed for just one to be thoroughly eradicated) as well as having severe health consequences for rural residents and affecting land use for decades.

InSight Crime Analysis

Despite the crop substitution program’s effectiveness and the compliance of the enrolled families, the government is doubling down.

But other pressures have come to threaten the crop substitution program. Pressure from criminal organizations, the lack of institutional articulation and deteriorating safety in key areas are the main threats identified for its implementation in rural municipalities. In the first months of 2018, the UNODC reported a 40 percent increase in homicides in municipalities implementing crop substitution.

The murder of social leaders in these regions, many of which supported and had personally advocated for the substitution programs, has been particularly high. More than 200 such murders have been registered since the peace agreement’s signing.

SEE ALSO: Coverage of Drug Policy

According to the UN, there have been close to 30 killings of social leaders in 2019 so far. And despite the severity and systematic nature of these assassinations, the government seems to have no plan to deal with this crisis and does not even view it as a priority, according to Amnesty International.

Over the past 10 years, forced eradication has also led to at least 126 deaths and 664 injuries among security forces and civilians participating in the operations. According to former president Juan Manuel Santos, these same areas have presented the highest proportion of anti-personnel mines.

One sign of the government’s unwillingness to comply with the crop substitution programs was the recent firing of the PNIS’ director, Claudia Salcedo, after she publicly corrected Defense Minister Guillermo Botero, in relation to the cost of eradicating a hectare of coca plants through glyphosate. At a public hearing in Congress, the minister stated that eradicating a hectare of coca glyphosate only cost $800, but Botero said the cost could reach $25,000.

Even Salcedo’s estimate seems low when taking into account the elevated social and economic costs of such operations, including military deployment, the purchase of fuel and glyphosate, logistics and evacuating an area. Alejandro Gaviria, Colombia’s health minister, has stated that the eradication of a single hectare of coca could reach up to $70,000.